It was nearly thirty-seven years back that I headed towards the Naval Academy at Cochin to join the Navy as an officer in the Executive Branch. I was to be part of the Eighth Integrated Course, equivalent of the Forty-sixth Course at NDA. Two years before that, I could have joined the Forty-second Course at NDA but even though I was in the merit list, my father did not permit me. He was of the rigid view that military was only for the brainless and the loony. His view, though coarse, found an echo in the writings of eminent authors of that era. I was fond of reading many of these since I was really fascinated by the navy. Taste this:

“The navy is for the mad. The mad and the loony. If you are not mad and find yourself in the Navy, you can only do well by pretending to be one.”

One reason that I could join when I did was that in addition to becoming a little more independent (a totally misleading word as compared to today’s scenario with children; independent then meant that you could float in a degree of false freedom until your parents would pull the plug), I was First in the Merit in the Indian Navy Entrance Exam.

I was awarded the Silver Medal for Academic Excellence when I passed out of the Naval Academy. Many years later I found the medal hidden away in my dad’s things. When I questioned him he said something about the misplaced pride that I could get by displaying it when I was merely “andhon mein kana raja” (a one-eyed king in the land of the blind). JP my younger brother did my father proud by becoming an academician (he is now an Associate Professor at the Georgetown University). Many years later I graduated from the Staff College with the Lentaigne; but, I am sure my father would have held that too with equal disdain.

The navy had a quaint way of looking at things and had equally esoteric language. “Aye aye, Sir”, “One to six heave”, cabins, bunks, starboard, coxswain, “very good” “avast lowering”, and “marry the falls” sounded strange then. To this list sailors had added their own, eg, “Contact designated as Reno Alpha”, “go by walk” and “Dinning Room”. Some are strange even today, eg, “Officers’ Married Accommodation” gives the impression of inanimate buildings having tied the knot.

The navy, I discovered, abhorred long words and expressions as these were considered totally unnecessary. During our parade training, the Chief GI Harbhajan Singh had only to bellow, through clenched teeth, the order “Peeeeeeeee” and we soon understood that he wanted us to “press your heels”. Senior Cadet A Mehrotra could spend an entire afternoon ragging me by using just one mono-syllabic word “so?”. Opening dialogues of an entire afternoon’s conversation in his cabin, whereat I performed such physical feats as “front-rolls” and “on your haunches”, went like this:

A: Cadet Ravi, I asked you to report to me at 1400 hrs. Now it is ten seconds past 1400 hrs. What do you have to say? (He was visibly exhausted by using these long sentences but these were the last ones he used that afternoon).

Me: Sir, I was going after lunch to my roo..er..cabin, and I slipped.

A: So?

Me: I broke my leg, Sir.

A: So?

Me: I was rushed to the hospital, Sir.

A: So?

Me: They took an X-Ray, Sir, and my leg has been put in a restraining bandage for a week.

A: So?

He indicated to me with his hand the now familiar sign for front-roll and I pointed at the leg-in-bandage. He was enraged beyond words and his lips were rounded to utter again the familiar mono-syllable. I had no choice and wincing in pain I started doing the front-roll. As I did the first one his expression changed from interrogative to joyous exclamation…”So!” I also discovered that afternoon that Sr Cadet A M also knew more about the self healing qualities of my leg than the doctors at INHS Sanjivini. As I emerged from his cabin two hours and many acrobatics later it surprised me to know that the ruddy leg pained the least in comparison to many other parts of my body.

That afternoon I silently conjured in my mind a quick and sure cure for a bad headache: ‘Hit yourself on the foot with a hammer’. Even for complex afflictions such as depression and bulimia the Navy has excellent cures.

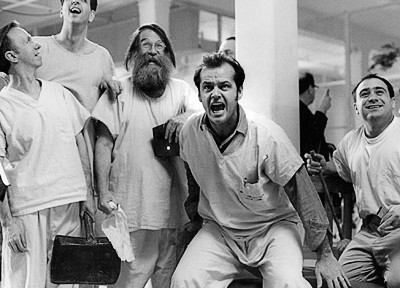

A few years after I joined I saw a very powerful movie called ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’. Thirty-seven years after joining the loony bunch as I woke up this morning, the morning of my first day as a retired officer I asked myself if I had actually flown over the Cuckoo’s Nest or lost my beans or marbles forever. It felt like a badly aching tooth having been finally pulled out; you not only miss the tooth but also the slow ache it used to cause. For many days after it is pulled out the tongue keeps going back to the place where it used to be and rekindle the pain.

Oh, how we used to do the countdown, as we stood on the Cadet Training Ship Delhi with a six-inch shell each on either shoulder. It was called the DLTGH – Days Left to Go Home. On my farewell, thirty-four years later, when the question of going home arose I had to acknowledge that the navy was the home and somewhere during my time in the navy DLTGH ceased to have its earlier meaning.

It is then that I started asking myself if I really belonged or belong. Subbu told me in the boat from Karanja after my farewell party that as compared to the Army we did not really have a sense of belonging. But that’s always been the lure of the seas. Remember Robert Browning’s Cristina?

“… That the Sea feels” –no “strange yearning

That such souls have, most to lavish

Where there’s chance of least returning”.

The Navy is also probably closer to Life. This kind of detachment is manifested in the words of the old Hindi song:

“Khatam huye din us dali per jis per tera basera tha,

Aaj yahan aur kal ho wahan yeh jogi wala phera tha,

Yeh teri jaagir nahin thi, chaar ghadi ka dera tha.

Kisko pata ab is nagri mein kab ho tera aana..

Chal udhja re panchhi ke ab yeh des hua begana.”

I was to become a Communicator – a kind of independent choice given to me by my Captain on Himgiri as my father was used to giving me. I understood the importance of my job through the ditty of the Railway Signaler:

It is not my job to run the train,

The whistle I cannot blow,

It is not my place to say how far,

The train’s allowed to go.

It is not my job to shoot off steam,

Not even to clang the bell,

But let the damn thing jump the track

And see who catches hell!

I came across many an ASW or Gunnery or ND officer who could have done wonders in their tasks if only the signal had reached them in time! I do not want to sound parochial but I have a feeling that your very character changes depending upon which branch you join! As a Communicator you learn to take all things in your stride because the buck stops at you; you have no one else to blame. For example, when I handed over the P&C File to Subbu I realized that as compared to my predecessors I had made nil letters to higher authorities on issues concerning officers and sailors.

Somewhere along, I cannot place when, the Navy claimed me totally. It did not matter who thought what of me; I became consumed by the naval ethos. I thoroughly enjoyed working for the Navy. A senior officer exhorted me at this stage to “let my hair down and relax”. I was reminded of following passage from ‘Lust For Life’, the biographical novel of Vincent Van Gogh:

“He had an excellent ability to paint. He’d get tired, he’d paint some more; he’d get fatigued he’d paint some more; he’d get exhausted he’d paint some more. After that he would be relaxed and could go back to his painting.”

A person was climbing a hill with a guide. Half way through he was in a thick forest with thorny bushes and sharp rocks. The going was tough. Exasperated he turned to the guide and said, “Where is that wonderful scenery that you were talking about?” And the guide said, “You are standing in it now, which you will see when you reach the top.”

Today, when I have detached myself from the thick jungles of day-to-day goings on in the navy I look back and really marvel at the scenery. I have no desire to fly over the cuckoo’s nest. The loony bunch is family, for heaven’s sake.

“I have come home, dad. I belong to the navy simply because I cannot belong anywhere else. Not now, after seven and thirty years. And dad many of them know words other than mono-syllables. Indeed, yesterday at the end of my farewell Billoo used more words for me than I would have used for myself.”